Version 2.1 dated 24 May 2023 – Go to the official PDF version.

Executive Summary

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) has adopted these guidelines to harmonise the methodology supervisory authorities use when calculating of the amount of the fine. These Guidelines complement the previously adopted Guidelines on the application and setting of administrative fines for the purpose of the Regulation 2016/679 (WP253), which focus on the circumstances in which to impose a fine.

The calculation of the amount of the fine is at the discretion of the supervisory authority, subject to the rules provided for in the GDPR. In that context, the GDPR requires that the amount of the fine shall in each individual case be effective, proportionate and dissuasive (Article 83(1) GDPR). Moreover, when setting the amount of the fine, supervisory authorities shall give due regard to a list of circumstances that refer to features of the infringement (its seriousness) or of the character of the perpetrator (Article 83(2) GDPR). Lastly, the amount of the fine shall not exceed the maximum amounts provided for in Articles 83(4) (5) and (6) GDPR. The quantification of the amount of the fine is therefore based on a specific evaluation carried out in each case, within the parameters provided for by the GDPR.

Taking the abovementioned into account, the EDPB has devised the following methodology, consisting of five steps, for calculating administrative fines for infringements of the GDPR.

Firstly, the processing operations in the case must be identified and the application of Article 83(3) GDPR needs to be evaluated (Chapter 3). Second, the starting point for further calculation of the amount of the fine needs to be identified (Chapter 4). This is done by evaluating the classification of the infringement in the GDPR, evaluating the seriousness of the infringement in light of the circumstances of the case, and evaluating the turnover of the undertaking. The third step is the evaluation of aggravating and mitigating circumstances related to past or present behaviour of the controller/processor and increasing or decreasing the fine accordingly (Chapter 5). The fourth step is identifying the relevant legal maximums for the different infringements. Increases applied in previous or next steps cannot exceed this maximum amount (Chapter 6). Lastly, it needs to be analysed whether the calculated final amount meets the requirements of effectiveness, dissuasiveness and proportionality. The fine can still be adjusted accordingly (Chapter 7), however without exceeding the relevant legal maximum.

Throughout all abovementioned steps, it must be borne in mind that the calculation of a fine is no mere mathematical exercise. Rather, the circumstances of the specific case are the determining factors leading to the final amount, which can – in all cases – be any amount up to and including the legal maximum.

These Guidelines and its methodology will remain under constant review of the EDPB.

The European Data Protection Board

Having regard to Article 70(1)(k), (1)(j) and (1)(e) of the Regulation 2016/679/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC, (hereinafter referred to as the “GDPR”),

Having regard to the EEA Agreement and in particular to Annex XI and Protocol 37 thereof, as amended by the Decision of the EEA joint Committee No 154/2018 of 6 July 2018.

Having regard to Article 12 and Article 22 of its Rules of Procedure,

Having regard to Article 29 Working Party Guidelines on the application and setting of administrative fines for the purposes of the Regulation 2016/679, WP253, which were endorsed by the European Data Protection Board (hereinafter referred to as the “EDPB”) at its first Plenary meeting,

HAS ADOPTED THE FOLLOWING GUIDELINES

CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION

1.1 – Legal framework

- The EU has – with the General Data Protection Regulation (hereinafter referred to as the “GDPR”), which has been applicable since 25 May 2018 – completed a comprehensive reform of data protection regulation in Europe. The protection of natural persons in relation to the processing of personal data is a fundamental right. The Regulation rests on several key components, one being stronger enforcement powers for supervisory authorities. The Regulation imposes a new, substantially increased level of fines, as well as providing for harmonization of fines between Member States.

- Data controllers and data processors have increased responsibilities to ensure that the personal data of the individuals are protected effectively. Supervisory authorities have powers to ensure that the principles of the GDPR as well as the rights of the individuals concerned are upheld according to the wording and the spirit of the GDPR.

- Therefore, the EDPB developed guidance to provide a clear and transparent basis for the supervisory authorities’ setting of fines. The previously published Guidelines on the application and setting of administrative fines address the circumstances in which an administrative fine would be an appropriate tool and interpret the criteria of Article 83 GDPR in this respect 2 . The present Guidelines address the methodology for the calculation of administrative fines. The two sets of Guidelines are applicable simultaneously and should be seen as complementary.

1.2 – Objective

- These Guidelines are intended for use by the supervisory authorities to ensure a consistent application and enforcement of the GDPR and express the EDPB’s common understanding of the provisions of Article 83 GDPR.

- The aim of these Guidelines is to create harmonised starting points as a common orientation, on the basis of which the calculation of administrative fines in individual cases can take place. However, it is settled case law that any such guidance need not be as specific as to allow a controller or processor to make a precise mathematical calculation of the expected fine. It is emphasised throughout these Guidelines that the final amount of the fine depends on all the circumstances of the case. The EDPB therefore envisages harmonisation on the starting points and methodology used to calculate a fine, rather than harmonisation on the outcome.

- These Guidelines can be seen as following a step-by-step approach, though supervisory authorities are not obliged to follow all steps if they are not applicable in a given case, nor to provide reasoning surrounding aspects of the Guidelines that are not applicable. Although, reasoning should at least include the factors which led to determining the level of seriousness, the turnover which is applied, and the aggravating and mitigating factors that were applied.

- Notwithstanding these Guidelines, supervisory authorities remain subject to all procedural obligations under national and EU law, including the duty to state reasons for their decisions and their obligations under the one stop shop mechanism. In that light, although the supervisory authorities are required to provide sufficient reasoning for their findings in accordance with national and EU law, these guidelines should not be interpreted as requiring the supervisory authority to state the exact starting amount or quantify the precise impact of each aggravating or mitigating circumstance. Moreover, mere reference to these Guidelines cannot replace the reasoning to be provided in a specific case.

- The Guidelines will be reviewed on an ongoing basis, as practices in the EU and the EEA are developed. It should be noted that, with the exception of Denmark and Estonia, supervisory authorities are authorised to issue administrative fines1)Footnote 4 – See Recital 151 GDPR., which are binding if not appealed. Thus, over time, both administrative and judicial practice will further develop.

1.3 – Scope

- These Guidelines are intended to govern and lay the foundation of the supervisory authorities’ setting of fines on an overarching level. The guidance set out applies to all types of controllers and processors according to Article 4(7) and (8) GDPR except natural persons when they do not act as undertakings. This is not withstanding the powers of national authorities to fine natural persons.

- According to Article 83(7) GDPR, each Member State may lay down the rules on whether and to what extent administrative fines may be imposed on public authorities and bodies established in that Member State. Provided that supervisory authorities have this power on the basis of national law, these Guidelines apply to the calculation of the fine to be imposed on public authorities and bodies, with the exception of Chapter 4.3. Supervisory authorities remain free, however, to apply a methodology similar to the one described in this Chapter. In addition, Chapter 6 is not applicable to the calculation of the fine to be imposed on public authorities and bodies, in case national law provides for different legal maximums and the public authority or body does not act as an undertaking as defined in Chapter 6.2.1.

- The Guidelines cover cross border cases as well as non-cross border cases.

- The Guidelines are not exhaustive, neither will they provide explanations about the differences between national administrative, civil or criminal law systems when imposing administrative sanctions in general.

1.4 – Applicability

- According to Article 70(1)(e) GDPR, the EDPB is empowered to issue guidelines, recommendations and best practices in order to encourage consistent application of the GDPR. Article 70(1)(k) GDPR specifies that the Board shall ensure the consistent application of the GDPR and shall, on its own initiative or, where relevant, at the request of the European Commission, in particular, draw up guidelines for supervisory authorities concerning the application of measures referred to in Article 58 and the setting of administrative fines pursuant to Article 83.

- In order to achieve a consistent approach to the imposition of administrative fines that adequately reflects all of the principles in the GDPR, the EDPB has agreed on a common understanding of the assessment criteria in Article 83 GDPR. The individual supervisory authorities will reflect this common approach, in accordance with the local administrative and judicial laws applicable to them.

CHAPTER 2 – METHODOLOGY FOR CALCULATING THE AMOUNT OF THE FINE

2.1 – General considerations

- Notwithstanding cooperation and consistency duties, the calculation of the amount of the fine is at the discretion of the supervisory authority. The GDPR requires that the amount of the fine shall in each individual case be effective, proportionate and dissuasive (Article 83(1) GDPR). Moreover, when setting the amount of the fine, supervisory authorities shall give due regard to a list of circumstances that refer to features of the infringement (its seriousness) or of the character of the perpetrator (Article 83(2) GDPR). The quantification of the amount of the fine is therefore based on a specific evaluation carried out in each case, taking account of the parameters included in the GDPR.

- For conduct infringing data protection rules, the GDPR does not provide for a minimum fine. Rather, the GDPR only provides for maximum amounts in Article 83(4)–(6) GDPR, in which several different types of conduct are grouped together. A fine can ultimately only be calculated by weighing up all the factors expressly identified in Article 83(2)(a)–(j) GDPR, relevant to the case and any other relevant elements, even if not explicitly listed in the said provisions (as Article 83(2)(k) GDPR requires to give due regard to any other applicable factor). Finally, the final amount of the fine resulting from this assessment must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive in each individual case (Article 83(1) GDPR). Any fine imposed must sufficiently take into account all of these parameters, whilst at the same time not exceeding the legal maximum provided for in Article 83(4)–(6) GDPR.

2.2 – Overview of the methodology

- Taking into account these parameters, the EDPB has devised the following methodology for calculating administrative fines for infringements of the GDPR.

- Step 1 – Identifying the processing operations in the case and evaluating the application of Article 83(3) GDPR. (Chapter 3)

- Step 2 – Finding the starting point for further calculation based on an evaluation of **(Chapter 4)**a) the classification in Article 83(4)–(6) GDPR;b) the seriousness of the infringement pursuant to Article 83(2)(a), (b) and (g) GDPR;c) the turnover of the undertaking as one relevant element to take into consideration with a view to imposing an effective, dissuasive and proportionate fine, pursuant to Article 83(1) GDPR.

- Step 3 – Evaluating aggravating and mitigating circumstances related to past or present behaviour of the controller/processor and increasing or decreasing the fine accordingly. (Chapter 5)

- Step 4 – Identifying the relevant legal maximums for the different processing operations. Increases applied in previous or next steps cannot exceed this amount. (Chapter 6)

- Step 5 – Analysing whether the final amount of the calculated fine meets the requirements of effectiveness, dissuasiveness and proportionality, as required by Article 83(1) GDPR, and increasing or decreasing the fine accordingly. (Chapter 7)

2.3 – Infringements with fixed amounts

- In certain circumstances, the supervisory authority may consider that certain infringements can be punished with a fine of a predetermined, fixed amount. The application of a fixed amount to certain types of infringements cannot hamper the application of the GDPR, in particular, Article 83 thereof. Moreover, applying fixed amounts does not relieve supervisory authorities from complying with cooperation and consistency (Chapter VII GDPR).

- It is at the discretion of the supervisory authority to establish which types of infringements can be punished with a predetermined fixed amount , based on their nature, gravity and duration. The supervisory authority cannot make such a determination if this is prohibited or would otherwise conflict with the national law of the Member State.

- Fixed amounts can be established at the discretion of the supervisory authority, taking into account – inter alia – the social and economic circumstances of that particular Member State, in relation to the seriousness of the infringement as construed by Article 83(2)(a), (b) and (g) GDPR. It is recommended that the supervisory authority communicates the amounts and circumstances for application beforehand.

CHAPTER 3 – CONCURRENT INFRINGEMENTS AND THE APPLICATION OF ARTICLE 83(3) GDPR

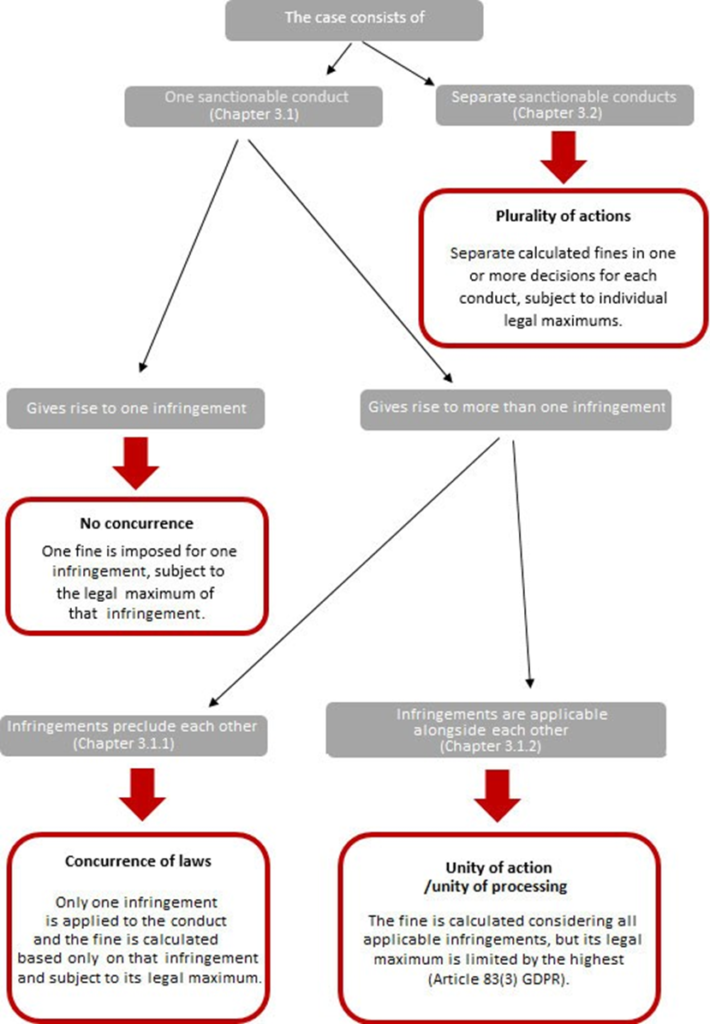

- Before being able to calculate a fine based on the methodology of these guidelines, it is important to first consider what conduct (factual circumstances regarding the behaviour) and infringements (abstract legal descriptions of what is sanctionable) the fine is based upon. Indeed, a particular case might include circumstances that could either be considered as one and the same or separate sanctionable conducts. Also, it is possible that one and the same conduct could give rise to a number of different infringements where the attribution of one infringement precludes attribution of another infringement or can be attributed alongside each other. In other words, there can be cases of concurrent infringements. Depending on the rules of concurrences such can lead to different calculations of fines.

- Examining the analysis of Member States’ traditions of rules on concurrences as outlined in CJEU case-law, and considering the different scopes of application and legal consequences, these principles can be roughly grouped into the following three categories:

- Concurrence of offences (Chapter 3.1.1),

- Unity of action (Chapter 3.1.2),

- Plurality of actions (Chapter 3.2).

- These different categories of concurrences do not conflict with each other, but have different scopes of application and fit into place in a coherent overall system, providing for a logical testing scheme.

- Therefore, it is important to first establish

a. Whether or not the circumstances are to be considered as one (Chapter 3.1) or multiple sanctionable conducts (Chapter 3.2),

b. In case of one conduct (Chapter 3.1), whether or not this conduct gives rise to one or more infringements, and

c. In case of one conduct that gives rise to multiple infringements, attribution of one infringement precludes the attribution of another infringement (Chapter 3.1.1) or whether they are to be attributed alongside each other (Chapter 3.1.2).

3.1 – One sanctionable conduct

- As a first step, it is essential to establish whether there is one and the same sanctionable conduct (“idem”) or there are multiple ones in order to identify the relevant sanctionable behaviour to be fined. Therefore, it is important to understand what circumstances are considered as one and the same conduct, as opposed to multiple conducts. The relevant sanctionable behaviour needs to be assessed and identified on a case-by-case basis. For example, in a certain case, “the same or linked processing operations” might constitute one and the same conduct.

- The term “processing operation” is included in Article 4(2) GDPR, where “processing” is defined as “any operation or set of operations which is performed on personal data or on sets of personal data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction.”

- When assessing ”the same or linked processing operations”, it should be kept in mind that all obligations legally necessary for the processing operations to be lawfully carried out can be considered by the supervisory authority for its assessment of infringements, including for instance transparency obligations (e.g. Article 13 GDPR). This is also underlined by the phrase “for the same or linked processing operations”, which indicates that the scope of this provision includes any infringement that relates to and may have an impact on the same or linked processing operations.

- The term “linked” refers to the principle that a unitary conduct might consist of several parts that are carried out by a unitary will and are contextually (in particular, regarding identity in terms of data subject, purpose and nature), spatially and temporally related in such a close way that, from an objective standpoint, they would be considered as one coherent conduct. A sufficient link should not be assumed easily, in order for the supervisory authority to avoid infringement of the principles of deterrence and effective enforcement of European law. Therefore, these aspects of relations for a sufficient link need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Example 1a – The same or linked processing operations

A financial institution requests a credit check from a credit reporting agency (CRA). The financial institutionreceives this information and stores it in its system.Although the collection and storage of the creditworthiness data by the financial institution each are bythemselves processing operations, they form a set of processing operations that are carried out by a unitarywill and are contextually, spatially and temporally related in such a close way that, from an objectivestandpoint, they would be considered as one coherent conduct. Therefore, the processing operations performed by the financial institution are to be considered as being “linked” and form the same conduct.

Example 1b – The same or linked processing operations

A data broker decides to implement a new processing activity as follows: it decides to collect – as a third party – the consumer transaction history from dozens of retailers without a legal basis, to perform psychometric analysis to predict future behaviour of individuals, including political voting behaviour, willingness to quit their job and more. In the same decision, the data broker decides to not include this procedure in the records of processing activities, not to inform data subjects and to ignore any data subject access requests related to the new processing operations. The processing operations involved in this processing activity form a set of processing operations that are carried out by a unitary will and are contextually, spatially and temporally related. They are to be considered as being “linked” and forming the same conduct. This also includes the failure to register the processing activity in the records, to inform data subjects and to establish procedures to give effect to the right of access with regard to the new processing operations. These obligations have been infringed for linked processing operations.

Example 1c – Not the same or linked processing operations

(i) A building authority performs a background check of a job applicant. The background check also includes the political affinity, union membership and sexual orientation. (ii) Five days later, the building authority demands from its vendors (sole traders) excessive self-disclosure regarding their business deals with other entities, irrespective of any relevance to the contract with or compliance obligations of the building authority. (iii) Another week later, the building authority suffers a personal data breach. The network of the building authority is hacked – despite having adequate technical and organisational measures in place– and the hacker gains access to a system that processes personal data of citizens that had filed requests with the building authority. Despite the data were adequately encrypted in line with applicable standards, the hacker is able to break it with military decryption technology and sells the data in the dark net. The building authority refrains from notifying the supervisory authority, despite its obligation to do so. The processing operations concerned in this case i.e. the background check, the demands of self-disclosure from vendors and the failure to notify a personal data breach, are not contextually related. Therefore, they are not to be considered “linked”, but instead form different conducts.

- Where it is established that the circumstances of the case form one and the same conduct and give rise to a single infringement, the fine can be calculated based on that infringement and its legal maximum. However, if the circumstances of the case form one and the same conduct, but this conduct gives rise to not only one, but multiple infringements, it must be established whether the attribution of one infringement precludes attribution of another infringement (Chapter 3.1.1) or can they be attributed alongside each other (Chapter 3.1.2). Where the circumstances of the case form multiple conducts, they are to be considered a plurality of actions and handled in line with Chapter 3.2.

3.1.1 – Concurrence of Offences

- The principle of concurrence of offences (also referred to as “apparent concurrence” or “false concurrence”) applies wherever the application of one provision precludes or subsumes the applicability of the other. In other words, concurrence occurs already on the abstract level of statutory provisions. This could either be on grounds of the principle of specialty, subsidiarity or consumption, which often apply where provisions protect the same legal interest. In such cases, it would be unlawful to sanction the offender for the same wrongdoing twice.

- In such a case of concurrence of offences, the amount of the fine should be calculated only on the basis of the infringement selected according to above rules (superseding infringement)”.

Principle of specialty

- The principle of specialty (specialia generalibus derogant) is a legal principle that means that more specific provision (derived from the same legal act or different legal acts of the same force) supersedes a more general provision, although both pursue the same objective. The more specific infringement then is sometimes considered a “qualified type” to the less specific one. Qualified type of infringement might be subject to a higher tier of fine, higher legal maximum or more extensive period of limitation.

- However, sometimes by way of interpretation, specialty can also apply, where for reasons of nature and systematics one infringement is considered a qualification of an apparently more specific one, although its wording alone does not explicitly name an additional element.

- Where instead two provisions pursue autonomous objectives, this constitutes a differentiating factor that justifies the imposition of separate fines. For example, if an infringement of one provision automatically results in an infringement of the other, but the converse is not true, these infringements pursue autonomous objectives.

- These principles of specialty can only apply, if and as far as the objectives pursued by the concerned infringements are actually congruent in the individual case. As the data protection principles in Article 5 GDPR are established as overarching concepts, there can be situations where other provisions are a concretisation of such principle, but not circumscribing the principle in its entirety. In other words, a provision does not always define the full scope of the principle. Therefore, depending on the circumstances, in some cases, they overlap in a congruent way and one infringement might supersede the other, while in other cases, the overlap is only partial and therefore not fully congruent. As far as they are not congruent, there is no concurrence of offences. Instead, they can be applied alongside each other, when calculating the fine.

Principle of subsidiarity

- Another form of concurrence of offences is often referred to as the principle of subsidiarity. It applies were one infringement is considered subsidiary to another infringement. This could be either because the law formally declares subsidiarity or because subsidiarity is given for material reasons. The latter can be the case where the infringements have the same objective, but one contains a lesser accusation of immorality or wrongdoing (e.g. an administrative offence can be subsidiary to criminal offence, etc.).

Principle of consumption

- The principle of consumption applies in cases where the infringement of one provision regularly leads to the infringement of the other, often because one infringement is a preliminary step to the other.

3.1.2 – Unity of action – Article 83(3) GDPR

- Similar to the situation of concurrence of offences the principle of unity of action (also referred to as “ideal concurrence”) applies in cases where one conduct is caught by several statutory provisions, with the difference that one provision is neither precluded nor subsumed by the applicability of the other, because they do not fall in scope of the principles of specialty, subsidiarity or consumption and mostly pursue different objectives.

- The principle of unity of action was further specified on the level of secondary law in Article 83(3) GDPR in form of a “unity of processing”. It is important to understand that Article 83(3) GDPR is limited in its application and will not apply to every single case in which multiple infringements are found to have occurred, but only to those cases where multiple infringements have arisen from “the same or linked processing operations” as explained above. In these cases, the total amount of the administrative fine shall not exceed the amount specified for the gravest infringement.

- In some special cases, a unity of action might also be assumed, where a single action infringes the same statutory provision several times. This could be particularly the case, where circumstances form an iterative and congeneric infringement of the same statutory provision in a close spatial and temporal succession.

Example 2 – Unity of action

A controller sends bundles of marketing e-mails to groups of data subjects in different waves during the course of one day without having a legal ground and thereby infringes Article 6(1) GDPR with one unity of action several times.

- The wording in Article 83(3) GDPR does not seem to directly cover this latter case of a unity of action, since “several provisions” are not infringed. However, it would constitute unequal and unfair treatment, if an offender that by one action infringes different provisions that pursue different objectives would be privileged against an offender that infringes with the same action the same provision that pursues the same objective multiple times. To avoid inconsistency of legal principle and in order to comply with the fundamental right to equal treatment in the Charter, in such cases, Article 83(3) GDPR shall be applied mutatis mutandis.

- In case of a unity of action the total amount of the administrative fine shall not exceed the amount specified for the gravest infringement. “As regards the interpretation of Article 83(3) GDPR, the EDPB points out that the effet utile principle requires all institutions to give full force and effect to EU law”. In this regard, Article 83(3) GDPR must not be interpreted in a manner where “it would not matter if an offender committed one or numerous infringements of the GDPR when assessing the fine”.

- The term “total amount” implies that all the infringements committed have to be taken into account when assessing the amount of the fine, and the wording “amount specified for the gravest infringement” refers to the legal maximums of fines (e.g. Articles 83(4)–(6) GDPR). **Therefore, “although the fine itself may not exceed the legal maximum of the highest fining tier, the offender shall still be explicitly found guilty of having infringed several provisions and these infringements have to be taken into account when assessing the amount of the final fine that is to be imposed” 19 . While this is without prejudice to the duty for the supervisory authority imposing the fine to take into account the need for the fine to be proportionate, the other infringements committed cannot be discarded and instead have to be taken into account when calculating the fine.

3.2 – Multiple sanctionable conducts

- The principle of plurality of actions (also referred to as “Realkonkurrenz”, “factual concurrence” or “coincidental concurrence”) describes all cases not caught by the principles of concurrence of offences (Chapter 3.1.1) or Article 83(3) GDPR (Chapter 3.1.2).

- The only reason that these infringements are handled in one decision is by having coincidentally come to the attention of the supervisory authority at the same time without being the same or linked processing operations in the meaning of Article 83(3) GDPR. Therefore, the offender is found to have infringed several statutory provisions and separate fines are imposed according to the national procedure either in the same fining decision or separate fining decisions. Moreover, since Article 83(3) GDPR does not apply, the total amount of the administrative fine may exceed the amount specified for the gravest infringement (argumentum e contrario). Cases of plurality of actions do not pose any reason to privilege the offender with regard to the fining calculation. However, this is without prejudice to the obligation to still comply with the general principle of proportionality.

Example 3 – Plurality of action

After conducting a data protection inspection at the premises of a controller, the supervisory authority finds that the controller failed to establish a procedure for review and continued improvement of its website security, to provide Article 13 information to employees regarding HR data processing and to inform the supervisory authority of a recent data breach regarding its vendor data. None of the infringements is precluded or subsumed by way of specialty, subsidiarity or consumption. Also, they do not qualify as the same processing operation or linked processing operations: they do not form a unity of action, but a plurality of actions. The supervisory authority therefore will find the controller to have infringed by different conducts Articles 13, 32, and 33 GDPR. It will impose in its fining decision individual fines for each, without there being a single legal maximum applicable to their sum.

CHAPTER 4 – STARTING POINT FOR CALCULATION

- The EDPB considers that the calculation of administrative fines should commence from a harmonised starting point. This starting point forms the beginning for further calculation, in which all circumstances of the case are taken into account and weighted, resulting in the final amount of the fine to be imposed upon the controller or processor.

- The identification of harmonised starting points in these Guidelines does not and should not preclude supervisory authorities from assessing each case on its merits. The fine imposed upon a controller/processor can range from any amount until the legal maximum of the fine, provided that this fine is effective, dissuasive and proportionate. The existence of a starting point does not prevent the supervisory authority from lowering or increasing the fine (up to its maximum) if the circumstances of the case so require.

- The EDPB considers three elements to form the starting point for further calculation: the categorisation of infringements by nature under Articles 83(4)–(6) GDPR, the seriousness of the infringement (as discussed in section 4.2 below) and the turnover of the undertaking as one relevant element to take into consideration with a view to imposing an effective, dissuasive and proportionate fine, pursuant to Article 83(1) GDPR. These are outlined in Chapter 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3 below.

4.1 – Categorisation of infringements under Articles 83(4)–(6) GDPR

- Almost all of the obligations of the controllers and processors according to the Regulation are categorised according to their nature in the provisions of Article 83(4)–(6) GDPR. The GDPR provides for two categories of infringements: infringements punishable under Article 83(4) GDPR on the one hand, and infringements punishable under Article 83(5) and (6) GDPR on the other. The first category of infringements is punishable by a fine maximum of €10 million or 2% of the undertaking’s annual turnover, whichever is higher, whereas the second is punishable by a fine maximum of €20 million or 4% of the undertaking’s annual turnover, whichever is higher.

- With this distinction, the legislator provided a first indication of the seriousness of the infringement in an abstract sense. The more serious the infringement, the higher the fine is likely to be.

4.2 – Seriousness of the infringement in each individual case

- The GDPR requires the supervisory authority to give due regard to the nature, gravity and duration of the infringement, taking into account the nature, scope or purpose of the processing concerned, as well as the number of data subjects affected and the level of damage suffered by them (Article 83(2)(a) GDPR); the intentional or negligent character of the infringement (Article 83(2)(b) GDPR); and the categories of personal data affected by the infringement (Article 83(2)(g) GDPR). For the purposes of these Guidelines, the EDPB refers to these factors as the seriousness of the infringement.

- The supervisory authority has to review these factors in the light of the circumstances of the specific case and has to conclude – on the basis of this analysis – on the degree of seriousness as indicated in paragraph 60. In this respect, the supervisory authority may also consider whether the data in question was directly identifiable. Even though they are discussed individually in these Guidelines, in reality these factors are often intertwined and should be viewed in relation to the facts of the case as a whole.

4.2.1 – Nature, gravity and duration of the infringement

- Article 83(2)(a) GDPR is broad in scope and requires the supervisory authority to carry out a complete examination of all the elements that constitute the infringement and that are suitable to differentiate it from other infringements of the same kind. This assessment should therefore consider the following specific factors:

a) The nature of the infringement, assessed by the concrete circumstances of the case. In that sense, this analysis is more specific than abstract classification of Article 83(4)–(6) GDPR. The supervisory authority may review the interest that the infringed provision seeks to protect and the place of this provision in the data protection framework. In addition, the supervisory authority may consider the degree to which the infringement prohibited the effective application of the provision and the fulfilment of the objective it sought to protect.

b) The gravity of the infringement, assessed on the basis of the specific circumstances. As stated in Article 83(2)(a) GDPR, this concerns the nature of the processing, but also the “scope or purpose of the processing concerned as well as the number of data subjects affected and the level of damage suffered by them,” will be indicative of the gravity of the infringement.

i. The nature of the processing, including the context in which the processing is functionally based (e.g. business activity, non-profit, political party, etc.) and all the characteristics of the processing. When the nature of processing entails higher risks, e.g. where the purpose is to monitor, evaluate personal aspects or to take decisions or measures with negative effects for the data subjects, depending on the context of the processing and the role of the controller or processor, the supervisory authority may consider to attribute more weight to this factor. Further, a supervisory authority may attribute more weight to this factor when there is a clear imbalance between the data subjects and the controller (e.g., when the data subjects are employees, pupils or patients) or the processing involves vulnerable data subjects, in particular, children.

ii. The scope of the processing, with reference to the local, national or cross-border scope of the processing carried out and the relationship between this information and the actual extent of the processing in terms of the allocation of resources by the data controller. This element highlights a real risk factor, linked to the greater difficulty for the data subject and the supervisory authority to curb unlawful conduct as the scope of the processing increases. The larger the scope of the processing, the more weight the supervisory authority may attribute to this factor.

iii. The purpose of the processing, will lead the supervisory authority to attribute more weight to this factor. The supervisory authority may also consider whether the processing of personal data falls within the so-called core activities of the controller. The more central the processing is to the controller’s or processor’s core activities, the more severe irregularities in this processing will be. The supervisory authority may attribute more weight to this factor in these circumstances. There may be circumstances though, in which the processing of personal data is further removed from the core activities of the controller or processor, but significantly impacts the evaluation nonetheless (this is the case, for example, of processing concerning personal data of workers where the infringement significantly affects those workers’ dignity).

iv. The number of data subjects concretely but also potentially affected. The higher the number of data subjects involved, the more weight the supervisory authority may attribute to this factor. In many cases, it may also be considered that the infringement takes on “systemic” connotations and can therefore affect, even at different times, additional data subjects who have not submitted complaints or reports to the supervisory authority. The supervisory authority may, depending on the circumstances of the case, consider the ratio between the number of data subjects affected and the total number of data subjects in that context (e.g. the number of citizens, customers or employees) in order to assess whether the infringement is of a systemic nature.

v. The level of damage suffered and the extent to which the conduct may affect individual rights and freedoms. The reference to the “level” of damage suffered, therefore, is intended to draw the attention of the supervisory authorities to the damage suffered, or likely to have been suffered as a further, separate parameter with respect to the number of data subjects involved (for example, in cases where the number of individuals affected by the unlawful processing is high but the damage suffered by them is marginal).

Following Recital 75 GDPR, the level of damage suffered refers to physical, material or non-material damage. The assessment of the damage, in any case, be limited to what is functionally necessary to achieve correct evaluation of the level of seriousness of the infringement as indicated in paragraph 60 below, without overlapping with the activities of judicial authorities as tasked with ascertaining the different forms of individual harm.

c) The duration of the infringement, meaning that a supervisory authority may generally attribute more weight to an infringement with longer duration. The longer the duration of the infringement, the more weight the supervisory authority may attribute to this factor. Subject to national law, if a given conduct was also illicit within the previous regulatory framework, both the period after the GDPR’s effective date and the previous period may be taken into account when quantifying the fine, taking into account the conditions of that framework.

- The supervisory authority may attribute weight to the abovementioned factors, depending on the circumstances of the case. If not of particular relevance, they may also be considered as neutral.

4.2.2 – Intentional or negligent character of the infringement

- In its previous guidance, the EDPB stated that “in general, intent includes both knowledge and willfulness in relation to the characteristics of an offence, whereas ’unintentional’ means that there was no intention to cause the infringement although the controller/processor breached the duty of care which is required in the law.” ******Unintentional in this sense does not equate to non-voluntary.

Example 4 – Illustrations of intent and negligence (from WP 253)

“Circumstances indicative of intentional breaches might be unlawful processing authorised explicitly by the top management hierarchy of the controller, or in spite of advice from the data protection officer or in disregard for existing policies, for example obtaining and processing data about employees at a competitor with an intention to discredit that competitor in the market. Other examples here might be:– amending personal data to give a misleading (positive) impression about whether targets have been met – we have seen this in the context of targets for hospital waiting times– the trade of personal data for marketing purpose i.e. selling data as ‘opted in’ without checking/disregarding data subjects’ views about how their data should be usedOther circumstances, such as failure to read and abide by existing policies, human error, failure to check for personal data in information published, failure to apply technical updates in a timely manner, failure to adopt policies (rather than simply failure to apply them) may be indicative of negligence”;

- The intentional or negligent character of the infringement (Article 83(2)(b) GDPR) should be assessed taking into account the objective elements of conduct gathered from the facts of the case. The EDPB highlighted that it is generally admitted that intentional infringements, “demonstrating contempt for the provisions of the law, are more severe than unintentional ones”2)Footnote 25 – . In case of an intentional infringement, the supervisory authority is likely to attribute more weight to this factor. Depending on the circumstances of the case, the supervisory authority may also attach weight to the degree of negligence. At best, negligence could be regarded as neutral.

4.2.3 – Categories of personal data affected

- Concerning the requirement to take account of the categories of personal data affected (Article 83(2)(g) GDPR), the GDPR clearly highlights the types of data that deserve special protection and therefore a stricter response in terms of fines. This concerns, at the very least, the types of data covered by Articles 9 and 10 GDPR, and data outside the scope of these Articles the dissemination of which causes immediate damages or distress to the data subject (e.g. location data, data on private communication, national identification numbers, or financial data, such as transaction overviews or credit card numbers). In general, the more of such categories of data involved or the more sensitive the data, the more weight the supervisory authority may attribute to this factor.

- Further, the amount of data regarding each data subject is of relevance, considering that the infringement of the right to privacy and protection of personal data increases with the amount of data regarding each data subject.

4.2.4 – Classifying the seriousness of the infringement and identifying the appropriate starting amount

- The assessment of the factors above (Chapter 4.2.1–4.2.3) determines the seriousness of the infringement as a whole. This assessment is no mathematical calculation in which the abovementioned factors are considered individually, but rather a thorough evaluation of the concrete circumstances of the case, in which all of the abovementioned factors are interlinked. Therefore, in reviewing the seriousness of the infringement, regard should be given to the infringement as a whole.

- Based on the evaluation of the factors outlined above, the infringement is considered to be of a (i) low, (ii) medium, or (iii) high level of seriousness. These categories are without prejudice to the question whether or not a fine can be imposed.

- When calculating the administrative fine for infringements of a low level of seriousness, the supervisory authority will determine the starting amount for further calculation at a point between 0 and 10% of the applicable legal maximum.

- When calculating the administrative fine for infringements of a medium level of seriousness, the supervisory authority will determine the starting amount for further calculation at a point between 10 and 20% of the applicable legal maximum.

- When calculating the administrative fine infringements of a high level of seriousness, the supervisory authority will determine the starting amount for further calculation at a point between 20 and 100% of the applicable legal maximum.

- As a general rule, the more severe the infringement within its own category, the higher the starting amount is likely to be.

- The ranges within which the starting amount is determined remains under review by the EDPB and its members and can be adapted when necessary.

Example 5a – Qualifying the seriousness of an infringement (high level of seriousness)

After investigating numerous complaints about unsolicited calls from customers of a telephone company, the competent supervisory authority found that the telephone company used contact details of its customers for telemarketing purposes without a valid legal basis (infringement of Article6 GDPR). In particular, the telephone company had offered the names and registered phone numbers of its customers to third parties for marketing purposes. The telephone company did this despite advice against it from the data protection officer, without undertaking any efforts to curb the practice or to offer customers a way of objecting. In fact, the practice had been going on since May 2018 and was still ongoing at the time of the investigation. The telephone company in question operated nationwide and the practice affected all of its 4 million customers. The supervisory authority found that all of these customers had been regularly subjected to unsolicited calls by third parties, without any effective means to stop them.The supervisory authority was tasked with assessing the seriousness of this case. As a starting point, the supervisory authority noted that an infringement of Article 6 GDPR is listed among the infringements of Article 83(5) GDPR and therefore falls within the higher tier of Article 83 GDPR.Secondly, the supervisory authority assessed the circumstances of the case. In that regard, the supervisory authority attributed significant weight to nature of the infringement, as the infringed provision (Article 6 GDPR) underpins the legality of the data processing as a whole. Non-compliance with this provision removes the lawfulness of the processing as a whole. Also, the supervisory authority attributed significant weight to the duration of the infringement, which started at the entry into force of the GDPR and had not ceased at the time of the investigation. The fact that the telephone company operated nationwide increased the weight of the scope of the processing. The number of data subjects involved was considered very high (4 million, offset against a total population of 14 million people), while the level of damage suffered by them was considered moderate (non-material damage, in the form of nuisance). The latter assessment was made taking into account the categories of data affected (name and phone number). The seriousness of the infringement was increased, however, by the fact that the infringement was committed in contrary to an advice from the data protection officer and, thus, considered intentional.Taking all the above into account (serious nature, long duration, high number of data subjects, nationwide scope, intentional nature, vis-à-vis moderate damage), the supervisory concludes that the infringement is considered to be at a high level of seriousness. The supervisory authority will determine the starting amount for further calculation at a point between 20 and 100% of the legal maximum included in Article 83(5) GDPR.

Example 5b – Qualifying the seriousness of an infringement (medium level of seriousness)

A supervisory authority received a personal data breach notification from a hospital. From this notification, it appeared that several staff members had been able to view parts of patients’ health files that – based on their department – should not have been accessible to them. The hospital had been working on procedures to regulate access to patient files, and had implemented strict measures for restricted access. That entailed that staff from one department could only access medical information relevant to that specific department. In addition, the hospital had invested in privacy awareness amongst its staff members. However, as it turned out, there were issues concerning the monitoring of authorisations. Staff members that transferred between departments were still able to gain access to the patient files from their “old” departments and the hospital had no procedures in place to match the current position of the staff member with their authorisation. Internal investigation by the hospital showed that at least 150 staff members (out of the 3500) had inaccurate authorisations, affecting at least 20,000 of the 95,000 patient files. The hospital could show that in at least 16 instances staff members had used their authorisations to view patient files. The supervisory authority considers that there has been a breach of Article 32 GDPR.In assessing the seriousness of the case, the supervisory authority first noted that an infringement ofArticle 32 GDPR is listed among the infringements of Article 83(4) GDPR and therefore falls within the lower tier of Article 83 GDPR. Secondly, the supervisory authority assessed the circumstances oft he case. In that regard, the supervisory authority considered that even though the number of data subjects affected by the breach was only 16, this could potentially have been 20,000 in the circumstances of the case and even 95,000 given the systemic nature of the issue. Furthermore, the supervisory authority categorised the infringement as negligent, but to a low degree, which was considered a neutral factor in the circumstances of this particular case due to the fact that the hospital failed to adopt authorisation policies where it surely should have done so but had, otherwise, taken steps to implement strict measures to restrict access. This evaluation was not impacted by the fact that other data protection and security policies were implemented successfully, as the GDPR requires. Lastly, the supervisory authority attributed significant weight to the fact that the patient files include health data, which are special categories of data according to Article 9 GDPR. Taking all the above into account (nature of the processing and special categories of data vis-à-vis the number of data subjects actually and potentially affected, the supervisory authority concludes that the infringement is considered to be at a medium level of seriousness. The supervisory authority will determine the starting amount for further calculation at a point between 10 and 20% of the legal maximum included in Article 83(4) GDPR.

Example 5c – Qualifying the seriousness of an infringement (low level of seriousness)

A supervisory authority has received numerous complaints about the way in which an online store handles the right of access of its data subjects. According to the complainants, the handling of their access requests has taken between 4 and 6 months, which is outside the timeframe permitted by theGDPR. The supervisory authority investigates the complaints and finds that the online store responds to access requests a maximum of three months too late in 5% of the cases. In total the store received around 1,000 access requests on an annual basis and confirmed that 950 of these were handled ontime. Moreover, the online store had policies in place to safeguard that all access requests were handled correctly and fully. Nevertheless, the supervisory authority concluded that the online store infringed Article 12(3) GDPR and decided to impose a fine.During the calculation of the amount of the fine to be imposed, the supervisory authority was tasked with assessing the seriousness of this case. As a starting point, the supervisory authority noted that an infringement of Article 12 GDPR is listed among the infringements of Article 83(5) GDPR and therefore falls within the higher tier of Article 83 GDPR. Secondly, the supervisory authority assessed the circumstances of the case. In that regard, the supervisory authority carefully analysed the nature of the infringement. Even though the timely right to access to personal data is one of the cornerstones of the data subject rights, the supervisory authority considered that the infringement was of limited seriousness in this respect, given that all requests were handled eventually and with a limited delay. Considering the purpose of the processing, the supervisory authority found that the processing of personal data was not the core activity of the online store, but still an important ancillary in fulfilling its objective of selling goods online. The supervisory authority considered this to increase the seriousness of the infringement. On the other hand, the level of damage suffered by the data subjects was considered minimal, as all access requests were handled within 6 months.Taking all the above into account (nature of the infringement, purpose of the processing and level of damage), the supervisory authority concludes that the infringement is considered to be at a low level of seriousness. The supervisory authority will determine the starting amount for further calculation at a point between 0 and 10% of the legal maximum included in Article 83(5) GDPR.

4.3 – Turnover of the undertaking with a view to imposing an effective, dissuasive and proportionate fine

- The GDPR requires each supervisory authority to ensure that the imposition of administrative fines is effective, proportionate and dissuasive in each individual case (Article 83(1) GDPR). The application of these principles of European Union law can have far-reaching consequences in individual cases, as the starting points that the GDPR offers for calculating administrative fines apply to micro-enterprises and multinational corporations alike. In order to impose a fine that is effective, proportionate and dissuasive in all cases, supervisory authorities are expected to tailor administrative fines within the entire range available up until the legal maximum. This can lead to significant increases or decreases of the amount of the fine, depending on the circumstances of the case.

- The EDPB considers that it is fair to reflect a distinction of the size of the undertaking in the starting points identified below and therefore takes into account its turnover. The EDPB follows the requirements of Article 83 GDPR, the GDPR as a whole and the established case law of the CJEU stating that the turnover of an undertaking can constitute an indication of the size and economic power of an undertaking. However, this does not dismiss a supervisory authority from the responsibility to carry out a review of effectiveness, dissuasiveness and proportionality at the end of the calculation (see Chapter 7). The latter covers all the circumstances of the case, including e.g. the accumulation of multiple infringements, increases and decreases for aggravating and mitigating circumstances and financial/socio-economic circumstances. It is, however, incumbent upon the supervisory authority to ensure that the same circumstances are not counted twice. In particular, supervisory authorities should not, under Chapter 7, repeat the increases or decreases relative to the turnover of the company, but rather revisit their evaluation of the appropriate starting amount.

- For the reasons outlined above, the supervisory authority may consider adjusting the starting amount corresponding to the seriousness of the infringement in cases where this infringement is committed by an undertaking with an annual turnover not exceeding 2 million euros, an annual turnover not exceeding 10 million euros, or an annual turnover not exceeding 50 million euros.

- For undertakings with an annual turnover of ≤ €2m, supervisory authorities may consider to proceed calculations on the basis of a sum between 0.2% and 0.4% of the identified starting amount.

- For undertakings with an annual turnover of €2m up until €10m, supervisory authorities may consider to proceed calculations on the basis of a sum between 0.3% and 2% of the identified starting amount.

- For undertakings with an annual turnover of €10m up until €50m, supervisory authorities may consider to proceed calculations on the basis of a sum between 1.5% and 10% of the identified starting amount.

- For the same reasons, the supervisory authority may consider adjusting the starting amount corresponding to the seriousness of the infringement in cases where this infringement is committed by an undertaking with an annual turnover not exceeding 100 million euros, an annual turnover not exceeding 250 million euros and an annual turnover not exceeding 500 million euros.

- For undertakings with an annual turnover of €50m up until €100m, supervisory authorities may consider to proceed calculations on the basis of a sum between 8% and 20% of the identified starting amount.

- For undertakings with an annual turnover of €100m up until €250m, supervisory authorities may consider to proceed calculations on the basis of a sum between 15% and 50 % of the identified starting amount.

- For undertakings with an annual turnover of €250m up until €500m,, supervisory authorities may consider to proceed calculations on the basis of a sum between 40% and 100% of the identified starting amount.

- For undertakings with an annual turnover above €500m, supervisory authorities may consider to proceed without an adjustment of the identified starting amount. Indeed, such undertakings will exceed the static legal maximum and, thus, the size of the undertaking is already reflected in the dynamic legal maximum used to determine the starting amount for further calculation based on the evaluation of the seriousness of the infringement.

- As a general rule, the higher the turnover of the undertaking within its applicable tier, the higher the starting amount is likely to be. The latter holds particularly true for the largest of undertakings, for which the category of starting amounts has the widest range.

- Moreover, the supervisory authority is under no obligation to apply this adjustment if it is not necessary from the point of view of effectiveness, dissuasiveness and proportionality to adjust the starting amount of the fine.

- It should be reiterated that these figures are the starting points for further calculation, and not fixed amounts (price tags) for infringements of provisions of the GDPR. The supervisory authority has the discretion to utilise the full fining range from any amount until the legal maximum, ensuring that the fine is tailored to the circumstances of the case, as the Court of Justice requires in case an abstract starting point is used.

*Example 6a – Identifying the starting points for further calculation

A supermarket chain with a turnover of €450 million ***has infringed Article 12 GDPR. The supervisory authority, based on a careful analysis of the circumstances of the case, decided that the infringement is of a low level of seriousness. To determine the starting point for further calculation, the supervisory authority first identifies that Article 12 GDPR is listed in Article 83(5)(b) GDPR and that, based on the turnover of the undertaking (€450 million), a legal maximum of €20 million ,- applies.Based on the level of seriousness determined by the supervisory authority (low), a starting amount between €0 and €2 million,- should be considered (between 0 and 10% of the applicable legal maximum, see paragraph 60 above).The supervisory authority considers that an adjustment down to 90% of the starting amount is justified based on the size of the undertaking, which has a turnover of €450 million. This amount forms the basis for further calculation, which should result in a final amount not exceeding the applicable legal maximum of €20 million.

Example 6b – Identifying the starting points for further calculation

A start-up dating app with a turnover of €500,000,- is discovered to have sold sensitive personal data of its customers to several data brokers for analytics and thereby infringed Articles 9 and 5(1)(a)GDPR. The supervisory authority, based on a careful analysis of the circumstances of the case, decided that the infringement is of a high level of seriousness. To determine the starting point for further calculation, the supervisory authority first identifies that Articles 9 and 5 GDPR are listed inArticle 83(5)(a) GDPR and that, based on the turnover of the undertaking (€500,000,-), a legal maximum of €20,000,000,- applies.Based on the level of seriousness determined by the supervisory authority (high), a starting amount between €4,000,000,- and €20,000,000,- should be considered (between 20 and 100% of the applicable legal maximum, see paragraph 60 above).The supervisory authority considers that an adjustment down to 0.25 % of the starting amount is justified based on the size of the undertaking, which has a turnover of €500,000. This amount forms the basis for further calculation, which should result in a final amount not exceeding the applicable maximum of €20 million.

CHAPTER 5 – AGGRAVATING AND MITIGATING CIRCUMSTANCES

5.1 – Identification of aggravating and mitigating factors

- Following the structure of the GDPR, after having evaluated the nature, gravity and duration of the infringement as well as its intentional or negligent character of the infringement and the categories of personal data affected, the supervisory authority must take account of the remaining aggravating and mitigating factors as listed in Article 83(2) GDPR.

- With regard to the assessment of these elements, increases or decreases of a fine cannot be predetermined through tables or percentages. It is reiterated that the actual quantification of the fine will depend on all the elements collected during the course of the investigation and on further considerations also linked to previous fining experiences of the supervisory authority.

- For clarity, it should be noted that each criterion of Article 83(2) GDPR – whether it is assessed under Chapter 4 or this Chapter – should only be taken into account once as part of the overall assessment of Article 83(2) GDPR.

5.2 – Actions taken by controller or processor to mitigate damage suffered by data subjects

- A first step in determining whether aggravating or mitigating circumstances have occurred, is to review Articles 83(2)(c), which concerns “any action taken by the controller or processor to mitigate the damage suffered by data subjects.”

- As recalled in Guidelines WP253, data controllers and processors are already obliged to “implement technical and organisational measures to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk, to carry out data protection impact assessments and mitigate risks arising from the processing of personal data to the rights and freedoms of the individuals.” However, in case of an infringement, the controller or processor should “do whatever they can do in order to reduce the consequences of the breach for the individual(s) concerned.

- The adoption of appropriate measures to mitigate the damage suffered by the data subjects may be considered a mitigating factor, decreasing the amount of the fine.

- The measures adopted must be assessed, in particular, with regard to the element of timeliness, i.e. the time when they are implemented by the controller or processor, and their effectiveness. In that sense, measures spontaneously implemented prior to the commencement of the supervisory authority’s investigation becoming known to the controller or processor are more likely to be considered a mitigating factor, than measures that have been implemented after that moment.

5.3 – Degree of responsibility of the controller or processor

- Following Article 83(2)(d), the degree of responsibility of the controller or processor will have to be assessed, taking into account measures implemented by them pursuant to Articles 25 and 32 GDPR. In line with Guidelines WP253, “the question that the supervisory authority must then answer is to what extent the controller ‘did what it could be expected to do’ given the nature, the purposes or the size of the processing, seen in light of the obligations imposed on them by the Regulation”.

- In particular, with regard to this criterion, the residual risk for the freedoms and rights of the data subjects, the impairment caused to the data subjects and the damage persisting after the adoption of the measures by the controller as well as the degree of robustness of the measures adopted pursuant to Articles 25 and 32 GDPR must be assessed.

- In this respect, the supervisory authority may also consider whether the data in question was directly identifiable and/or available without technical protection. However, it should be borne in mind that the existence of such protection does not necessarily constitute a mitigating factor (see paragraph 82 below). This depends on all the circumstances of the case.

- In order to adequately assess the above elements, the supervisory authority should take into account any relevant documentation provided by the controller or processor, e.g. in the context of the exercise of their right of defence. In particular, such documentation could provide evidence of when the measures were taken and how they were implemented, whether there were interactions between the controller and the processor (if applicable), or whether there has been contact with the DPO or data subjects (if applicable).

- Given the increased level of accountability under the GDPR in comparison with Directive 95/46/EC, it is likely that the degree of responsibility of the controller or processor will be considered an aggravating or a neutral factor. Only in exceptional circumstances, where the controller or processor has gone above and beyond the obligations imposed upon them, will this be considered a mitigating factor.

5.4 – Previous infringements by the controller or processor

- Previous infringements are infringements already established before the decision is issued. In case of cooperation under Chapter VII GDPR, prior infringements are those already established before the draft decision (in the sense of Article 60 GDPR) is issued.

- According to Article 83(2)(e) GDPR, any relevant previous infringements committed by the controller or processor must be considered when deciding whether to impose an administrative fine and deciding on the amount of the administrative fine. Similar wording is found in Recital 148 GDPR.

5.4.1 – Time frame

- Firstly, regard must be given to the point in time when the prior infringement took place, considering that the longer the time between a previous infringement and the infringement currently being investigated, the lower its significance. Consequently, the longer ago the infringement was committed, the less relevance shall be given by the supervisory authorities. This assessment is left at the discretion of the supervisory authority, subject to applicable national- and European law and principles.

- However, since infringements committed a long time ago might still be of interest when assessing the “track record” of the controller or processor, fixed limitation periods are not to be set to this purpose. However, some national laws do prevent the supervisory authority from considering previous infringements after a settled period. Likewise, certain national laws impose a record deletion obligation after a certain period of time, which prevents the acting supervisory authorities from taking into account these precedents.

- For the same reason, it should be noted that infringements of the GDPR, since they will be more recent, must be considered as more relevant than infringements of the national provisions adopted for the implementation of Directive 95/46/EC (if national laws allow such infringements to be taken into account by the supervisory authority).

5.4.2 – Subject matter

- For the purpose of Article 83(2)(e) GDPR, previous infringements of either the same or different subject matter to the one being investigated might be considered as “relevant”.

- Even though all prior infringements might provide an indication about the controller’s or processor’s general attitude towards the observance of the GDPR, infringements of the same subject matter must be given more significance, as they are closer to the infringement currently under investigation, especially when the controller or processor previously committed the same infringement (repeated infringements). Thus, same subject-matter infringements must be considered as more relevant than previous infringements concerning a different topic.

- For example, the fact that the controller or the processor had failed in the past to respond to data subjects exercising their rights in a timely manner must be considered more relevant when the infringement being investigated refers also to a lack of response to a data subject exercising their rights than when it refers to a personal data breach.

- However, due account must be taken of previous infringements of a different subject matter, but that were committed in the same manner, as they might be indicative of persisting problems within the controller or processor organisation. For example, this would be the case for infringements arising as a consequence of having ignored the advice provided by the Data Protection Officer.

5.4.3 – Other considerations

- If considering a previous infringement of the national provisions adopted for the implementation of the Directive 95/46/EC, the supervisory authorities must take into account the fact that the requirements in the Directive and the GDPR might differ (if national laws allow such infringements to be taken into account by the supervisory authority).

- When considering the relevance of a previous infringement, the supervisory authority should take account of the status of the procedure in which the previous infringement was established – particularly of any measures taken by the supervisory authority or by the judicial authority – in accordance with national law.

- Previous infringements could also be considered when they were found by a different supervisory authority concerning the same controller/processor. For example, the lead supervisory authority dealing with an infringement through the cooperation (one-stop-shop) mechanism in accordance with Article 60 GDPR could take into account infringements previously determined in local cases, by another supervisory authority, concerning the same controller/processor. Likewise, infringements previously determined by the lead supervisory authority could be taken into account when a different authority must handle a complaint lodged with it in cases with only local impacts under Article 56(2) GDPR. Where there is no lead supervisory authority (for example, in case the controller or processor is not established in the European Union), supervisory authorities could also take into account infringements previously determined by another supervisory authority concerning the same controller/processor.

- The existence of previous infringements can be considered an aggravating factor in the calculation of the fine. The weight given to this factor is to be determined in view of the nature and frequency of the previous infringements. The absence of any previous infringements, however, cannot be considered a mitigating factor, as compliance with the GDPR is the norm. If there are no previous infringements, this factor can be regarded as neutral.

5.5 – Degree of cooperation with the supervisory authority in order to remedy the infringement and mitigate the possible adverse effects of the infringement

- Article 83(2)(f) requires the supervisory authority to take account of the degree of the controller’s or processor’s cooperation with the supervisory authority in order to remedy the infringement and mitigate the possible adverse effects of the infringement.

- Before further assessing the level of cooperation the controller or processor has established with the supervisory authority, it must be reiterated that a general obligation to cooperate is incumbent on the controller and the processor pursuant to Article 31 GDPR, and that lack of cooperation may lead to the application of the fine provided for in Article 83(4)(a) GDPR. It should therefore be considered that the ordinary duty of cooperation is mandatory and should therefore be considered neutral (and not a mitigating factor).

- However, where cooperation with the supervisory authority has had the effect of limiting or avoiding negative consequences for the rights of the individuals that might otherwise have occurred, the supervisory authority may consider this a mitigating factor in the sense of Article 83(2)(f) GDPR, thereby decreasing the amount of the fine. This may for instance be the case when a controller or processor “has responded in a particular manner to the supervisory authority’s requests during the investigation phase in that specific case which has significantly limited the impact on individuals’ rights as a result”.

5.6 – The manner in which the infringement became known to the supervisory authority

- Following Article 83(2)(h), the manner in which the infringement became known to the supervisory authority could be a relevant aggravating or mitigating factor. In assessing this, particular weight can be given to the question whether, and if so to what extent, the controller or processor notified the infringement out of its own motion, before the infringement was known to the supervisory authority by – for instance – a complaint or an investigation. This circumstance is not relevant when the controller is subject to specific notification obligations (such as in the case of personal data breaches according to Article 33) . In such cases, this notification should be considered as neutral. 99.Where the infringement became known to the supervisory authority by, for instance, a complaint or an investigation, this element should also, as a rule, be considered as neutral. The supervisory authority may consider this a mitigating circumstance if the controller or processor notified the infringement out of its own motion, prior to the supervisory authority’s knowledge of the case.

5.7 – Compliance with measures previously ordered with regard to the same subject matter

- Article 83(2)(i) GDPR states that “where measures referred to in Article 58(2) have previously been ordered against the controller or processor concerned with regard to the same subject-matter, compliance with those measures” must be considered when deciding whether to impose an administrative fine and deciding on its amount.

- As opposed to Article 83(2)(e) GDPR, this assessment only refers to measures that supervisory authorities themselves have previously issued to the same controller or processor with regard to the same subject matter.

- In this respect, the controller or processor might hold reasonable expectations that compliance with measures previously issued against them would prevent a same subject-matter infringement from taking place in the future. However, since compliance with measures previously ordered is mandatory for the data controller or processor, it should not be taken into account as a mitigating factor per se. On the contrary, a reinforced commitment on the part of the controller or processor in the fulfilment of previous measures is required for this factor to apply as mitigating, e.g. taking additional measures beyond those ordered by the supervisory authority.

- Conversely, non-compliance with a corrective power previously ordered may be considered either as an aggravating factor, or as a different infringement in itself, pursuant to Article 83(5)(e) and Article 83(6) GDPR. Therefore, due note should be taken that the same non-compliant behaviour cannot lead to a situation where it is punished twice.

5.8 – Adherence to approved codes of conduct or approved certification mechanisms